A RARE CASE OF REVOLUTIONARY POETRY

Slavoj Žižek

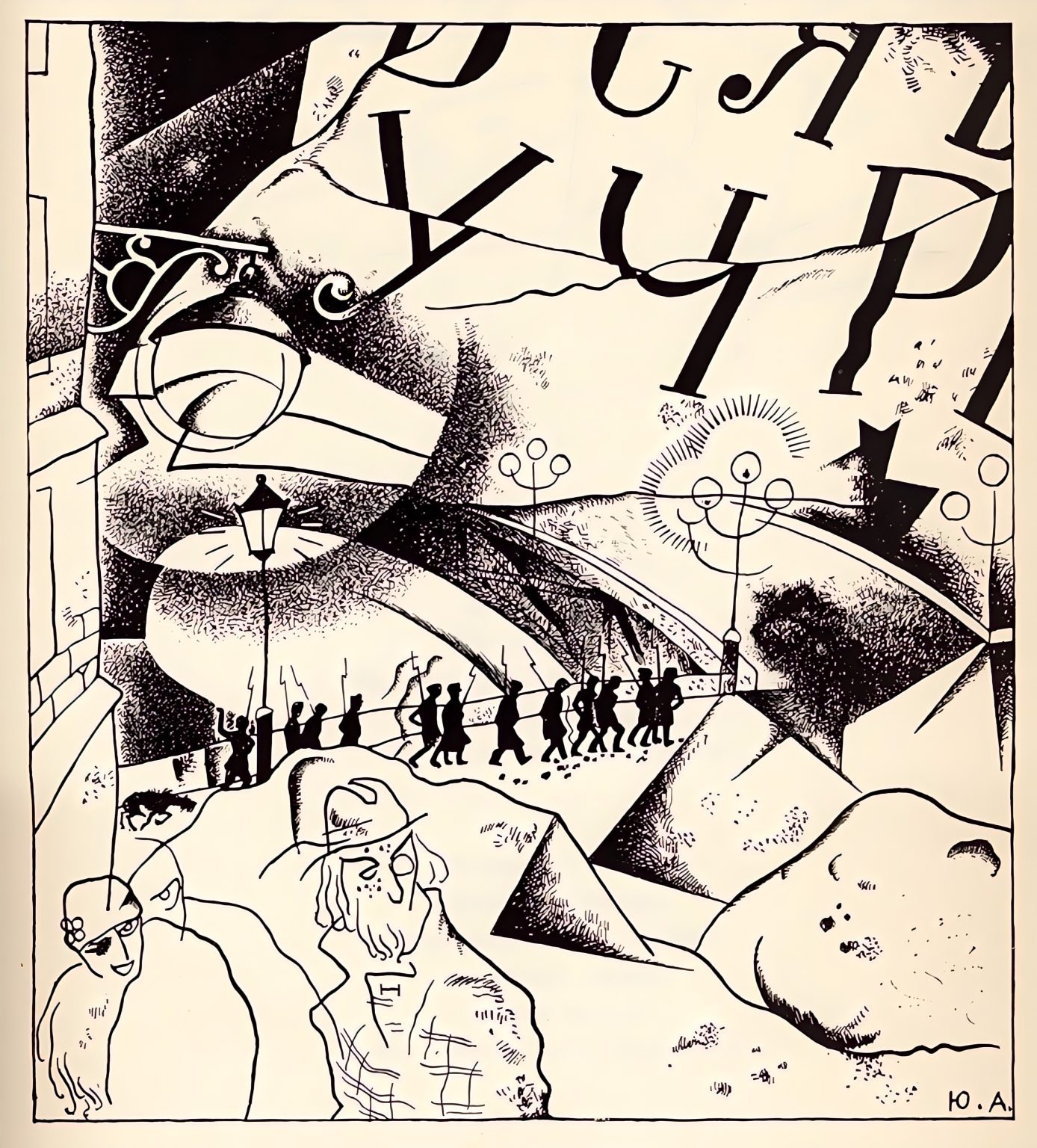

The immanent link between poetry and political struggle is perhaps best rendered by Twelve, a 1918 poem by Aleksandr Blok, one of the great Russian poets of the XXth century who considered it his best work. With its mood-creating sounds, polyphonic rhythms, and harsh, slangy language, the long (around 1000 verses) poem promptly alienated Blok from a mass of his admirers – accusations ranged from appallingly bad taste to servility before the new Bolshevik authorities and betraying his former ideals. But even the opposite side (most Bolsheviks) scorned Blok’s mysticism and asceticism and especially the mention of Christ (some Soviet reprints even replaced “Christ” by “sun”!). The poem describes the march of twelve Red Guards (likened to the Twelve Apostles) through the streets of revolutionary Petrograd in the snowy winter of 1918, with a fierce winter blizzard raging around them. The Twelve are not idealized, their mood as conveyed by the poem oscillates from base and even sadistic aggression towards everything perceived bourgeois and counter-revolutionary, to strict discipline and sense of revolutionary duty۱The Twelve (poem) – Wikipedia.. In the (most controversial) last stanza of the poem, a figure of Jesus Christ is seen in the snowstorm, heading the march of the Twelve as the invisible and undead thirteenth passenger, we might say:

“… And so they keep a martial pace, / Behind them follows the hungry dog, / Ahead of them — with bloody banner, / Unseen within the blizzard’s swirl, / Safe from any bullet’s harm, / With gentle step, above the storm, / In the scattered, pearl-like snow, / Crowned with a wreath of roses white, / Ahead of them — goes Jesus Christ۲Alexander Blok. Twelve. Translated by Maria Carlson (ruverses.com)..”

(An alternate translation of the last lines: “Soft-footed in the blizzard’s swirl, / Invulnerable where bullets sliced — / Crowned with a crown of snowflake pearl, / In a wreath of white rose, / Ahead of them Christ Jesus goes۳Alexander Blok. The Twelve. Translated by Jon Stallworthy and Peter France (ruverses.com)..”

John Ellison’s description of its social impact is worth quoting: “The poem first appeared in early March 1918 in a Bolshevik newspaper. Jack Lindsay wrote in his introduction to his own translation that it had ‘an immediate and vast effect. Phrases from it were endlessly repeated; hoardings and banners all over Russia bore extracts’. It became ‘the folklore of the revolutionary street’. In November 1918 The Twelve was published in its own right in Petrograd, adorned with Yuri Annenkov’s drawings. Forsyth states simply that it ‘became accepted as the essential expression of the Revolution, not only in Russia, where readers were either excited or disgusted by it, but also abroad۴Black night, white snow: Alexander Blok’s The Twelve (culturematters.org.uk). ’.”

Unfortunately, Blok was quickly disappointed by the Bolshevik Revolution, and his last work before his early death in 1921 was a patriotic poem “Scythians” which advocates a kind of “pan-Mongolism,” a clear precursor to today’s Eurasianism: Russia should mediate between East and West, but also politically between the Reds and the Whites. Already in its style, “Scythians” returns to more traditional poetic language with no common vulgar sounds and expressions, and no crazy rhythmic cuts – with none of what makes Twelve so unique.

In Twelve, we get a unique series of overlapping of the opposites: the poem praises the October Revolution, but it is as far as possible from the usual revolutionary pathetic, full of vulgar low-class language and course gestures. Christ is at the head of the group which patrols the Petrograd hell of natural and public chaos – let us not forget that their goal is to prevent social chaos, i.e., to maintain the new law and order. This is an authentic image of the theologico-political short-circuit, an image of what Christian atheism means as a political practice. Christ is not their leader, he is just a virtual shadow whose presence signals that the twelve are not just a group of individuals pursuing their particular interests but a group of comrades acting on behalf of a Cause. There is no promise or image of heavenly bliss in this image, it is just a group of comrades acting out of utter emergency, without any assurance of what the final outcome will be – maybe they will be liquidated by the enemy, or they will simply perish in the blizzard. Even if they are not aware of it, they act in their utter dedication as if Christ is at their head.

Even in the “developed” West, we recently encountered such groups which were inspecting locked-down areas for the victims of the pandemic, or looking for abandoned survivors of flooding and heat waves, or – why not – patrolling an area and searching for Russian mines on the Ukrainian front. And the list goes on: a group of artists engaged in a collective project, a group of programmers working on an algorithm that may help in our struggle for environment… Without thinking about it, they were and are just doing their duty.

Sketch for the poem “The Twelve” – Yuri Annenkov۵Born in 1889 – died in 1974 | Russian painter and designer – This work is part of a collection for the published edition of “The Twelve” in 1918.

This text has been prepared exclusively for Praxis Publication and Vazne Donya magazine.

To read the Farsi translation of this article, refer to the link below: