Feminist poetry for now

The relationship between feminist poetry and leftist approaches in the present era

Juliana Spahr

What is unique about poetry, in comparison to say the novel, is that no one publishes poetry with the idea that they could possibly someday get rich from book sales. And it has been true for a long time; certain forms of poetry exist only because rich people and the state are willing to fund its creation and dissemination for reasons other than profit. But it has also been true for a long time that sometimes poetry exists less because of patronage and more because of community support. The ramifications of these communities of interest vary. At moments these community poetries are closely tied to social movements. At other moments, they are created by poets with shared aesthetic concerns. In both instances, they can often be coterie-based, cliquish, and exclusionary. But despite all this variability, the fact that poetry can make it into the world through the kindness of some sort of community gives it a possibility of freedom. At moments this possibility of freedom feels as if it is more latent than real. But still, there are moments when this freedom empowers and it becomes obvious that this sort of poetry is ready-made for moments of protest against the state.

In the 1960s and 1970s, poetry mattered to feminism. And vice versa, feminism too mattered to certain poetries. This was especially true of what is often called “second-wave” feminism. Poetry in this era, just as second-wave feminism, defended more inclusive understandings of sexuality, family, and reproductive rights. Much of the poetry that came out of this moment resembled a version of confessionalism, especially the first-person lyrics of poets such as Anne Sexton or Sylvia Plath that focused on female experience. Like confessionalism, this second way feminist poetry was lyric in tonality and confessional in content and often written in the first person. But the difference was that poems were often about the relation of the author to the feminist movement. Audre Lorde’s poetry, for instance, was still often about herself and yet it was often also about civil rights, about sexual identity, about race. Adrienne Rich’s “Rape” is not just about rape, but it is also about the power dynamics between women and the state: “There is a cop who is both prowler and father: he comes from your block, grew up with your brothers, had certain ideals.”

This attention to the systemic as much as the personal defines also the more experimental feminist poems that show up in the 1980s and 1990s. Bernadette Mayer’s Midwinter Day is a poem that can easily be understood as confessional as it features a female narrator who chronicles her domestic labors during a single day. But its drive is more encyclopedic than lyric. It veers into the mundane. It often becomes loudly talky rather than quiet and reflective. It is more colloquial than mannered. In Alice Notley’s Descent of Alette, another feminist poem from this era, the female protagonist descends into the underworld to fight a tyrant. And as such the poem tells a feminist story as it rewrites epic conventions. But while these poems do a certain systemic work, they have not been seen as crucial to third-wave feminism in the way that Lorde or Rich were to the second-wave. My guess is that one reason for this is because their feminism is more gnarly and complex, less sloganistic, more focused on reproductive labor. But it also likely reflects the way that feminism itself had changed. It had succeeded enough that it was no longer a distinct community and thus no one poetry scene might be able to represent it.

My list of examples here is for sure arbitrary. And capricious too. But today, it seems to me that while poetry in the US holds feminist ideas, draws from a long feminist history, and is often written by people who identify as women about their experiences as women, the genre does not currently have a unique relationship to feminism. This does not mean that feminist poetry does not get written. Of course it does and Patricia Lockwood’s “Rape Joke” is one example. It paralleled #metoo, which, for better or worse, is the major feminist social movement of the twenty-first century. It is also hard not to notice that the systemic critique that defined Rich’s “Rape” has softened. The poem embraces not just irony but also satire. It is called “Rape Joke,” not just “Rape.” Still, despite the popularity of the poem, there is too much pressure on Lockwood’s poem to see it as a singular representative of a movement. Feminism itself has become something so diffuse, it is hard to find a poet or even a group of poets as its representative.

Where this leaves poetry and feminism in the US is unclear, but in a good way. Some recent work by trans writers have provocatively challenged second-wave and third-wave feminism and reductive understandings of gender. I do not want to insist that this work is necessarily feminist, especially as some of it is antagonistic towards various feminisms, especially the radical feminism of the second-wave. But feminism has a lot to learn from a work such as Violet Spurlock’s In Lieu of Solutions which dwells with the complexities of representing femaleness and refuses simplistic slogans. “What is not normal is the reduction of a body to hormone levels,” she writes, “What is not normal is the reduction of society to a vector complex”.

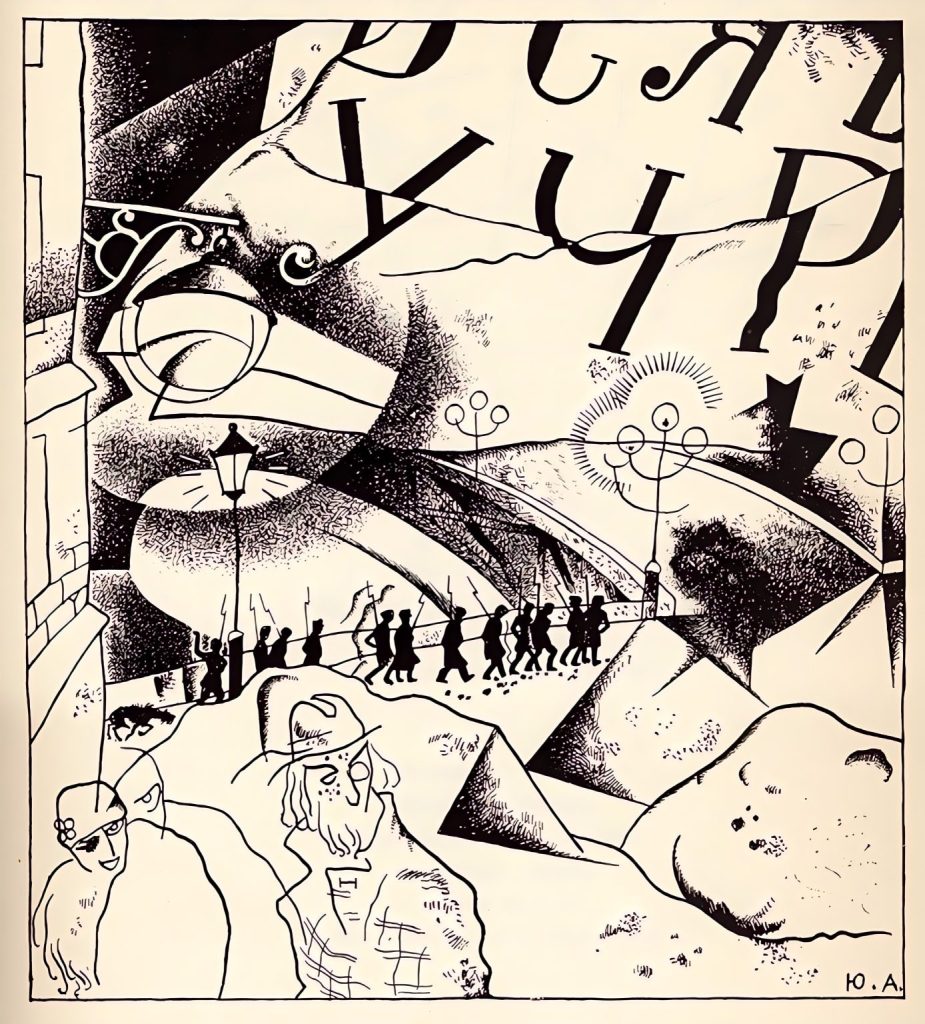

Threnody II | 1987 – By Leon Golub

This text has been prepared exclusively for Praxis Publication and Vazne Donya magazine.

To read the Farsi translation of this article, refer to the link below: